Un día, no importa cuál, decides emplear un poco de tu saturado tiempo en ver un debate televisivo, lo que te acarrea asumir la realidad de tu aislamiento político. A tu alrededor observas movimientos sociales y cómo muchas de tus personas cercanas disputan por si aquella ley es mejor que la otra, o si habría que suprimir una o modificar otra. Sea cual sea la cadena elegida, te encontrarás un grupo de personas que se gritan y no respetan su turno, que en realidad no están dispuestas a escuchar lo que dice el otro porque lo prioritario es anular la argumentación del contrario para lograr adeptos a su causa. Todas las cadenas han elegido un modelo de comunicación donde el consenso, la persuasión y el respeto no existen.

Leer más Archivo Histórico

Archivo Histórico

El geocentrismo y el heliocentrismo económico

El griego Ptolomeo fue el defensor de que la Tierra era el centro del universo y que el Sol giraba a su alrededor. En contra del geocentrismo Aristarco de Samos consideró que si se observaba la distancia entre la Tierra y el Sol podía deducirse que el centro de Universo no era la Tierra.

Leer másLiderazgo compartido – Shared management (226)

Cuando pensamos que estamos descubriendo un modo diferente de dirigir, y que todos los proyectos de desarrollo de personas son una innovación, sólo tenemos que volver nuestra mirada hacia otras culturas, para comprender que el hombre menos “civilizado” ya practica muchos de los principios que ahora vendemos como nuestros:

[1]Robert Dentan. The semai: A non-violent people of Malaya. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Nueva York, 1968

Estilos de liderazgo (203)

Kurtz Lewin, psicólogo polaco nacionalizado estadounidense, afirmaba que es imposible conocer al ser humano fuera de su entorno y de su hábitat natural y cotidiano. Lewin defendió que la conducta ha de entenderse como una constelación de variables independientes que conforman el campo dinámico. Esta teoría formulada por K. Lewin en el año 1939 y llamada Teoría de Campo remarcaba la importancia del estudio práctico para llegar a conclusiones sólidas e irrefutables en cualquier estudio sociológico.

Uno de sus numerosos experimentos relacionados con esta teoría y concernientes también con el liderazgo es el que se realizó en 1939 (lo podéis ver en el video «El poder de la situación», que ponemos al final del post). La pregunta que originó el experimento fue: ¿cómo es que los dictadores son capaces de moldear el comportamiento de los individuos dándoles una nueva identidad como miembros de un grupo? El objetivo era establecer los distintos tipos de liderazgo y observar la forma en la que las personas se comportan en los grupos ateniéndose al modelo de dirección.

Uno de sus numerosos experimentos relacionados con esta teoría y concernientes también con el liderazgo es el que se realizó en 1939 (lo podéis ver en el video «El poder de la situación», que ponemos al final del post). La pregunta que originó el experimento fue: ¿cómo es que los dictadores son capaces de moldear el comportamiento de los individuos dándoles una nueva identidad como miembros de un grupo? El objetivo era establecer los distintos tipos de liderazgo y observar la forma en la que las personas se comportan en los grupos ateniéndose al modelo de dirección.Liderar nuestra existencia (197)

Viktor Frankl se enfrentó a las humillaciones y vejaciones vividas en los campos de concentración nazi apropiándose de sus vivencias. Entendió que sus carceleros podían hacer con su cuerpo lo que quisieran, pero que en ningún caso podrían quitarle lo que dio en llamar su «libertad última». Frankl comprendió que en su interior él podía decidir de qué modo le afectaría todo aquello. Para ello, debía encontrar el sentido de su existencia global y el entendimiento de cada vivencia concreta.

Tendemos a rescindir nuestro contrato vital concediendo a los demás el poder de dirigir nuestras acciones, y no tanto porque aceptemos sus consejos, sino porque nuestros fracasos se los imputamos a los demás, o al menos buscamos compartir la carga del error con familiares, amigos, colaboradores, crisis externas, etc.

Tendemos a rescindir nuestro contrato vital concediendo a los demás el poder de dirigir nuestras acciones, y no tanto porque aceptemos sus consejos, sino porque nuestros fracasos se los imputamos a los demás, o al menos buscamos compartir la carga del error con familiares, amigos, colaboradores, crisis externas, etc.La ética y los nuevos modelos de liderazgo (168)

El pasado día 19, la Asociación para el Progreso de la Dirección (APD) convocó a algunos de los pensadores más conocidos para que reflexionaran sobre el reforzamiento de la sociedad civil. De las aportaciones que se fueron realizando resalto las que me parecieron más significativas referidas a la persona y a las estructuras sociales.

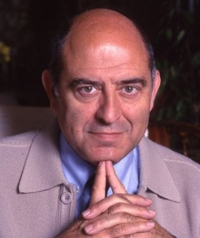

El filósofo Fernando Savater apuntó algunos de los valores que debía incorporar la sociedad para la conquista de una estructura moral.

El filósofo Fernando Savater apuntó algunos de los valores que debía incorporar la sociedad para la conquista de una estructura moral. José Antonio Marina centró su conferencia en la juventud, y remarcó que la familia española es superprotectora y amortiguadora de problemas, de tal modo que la juventud se alarga hasta los 31 años. Esto ha originado una impotencia confortable en los jóvenes y una ralentización del dinamismo social.

José Antonio Marina centró su conferencia en la juventud, y remarcó que la familia española es superprotectora y amortiguadora de problemas, de tal modo que la juventud se alarga hasta los 31 años. Esto ha originado una impotencia confortable en los jóvenes y una ralentización del dinamismo social.

0

0